Smallpox Eradication in Nigeria: Lessons for Immunisation

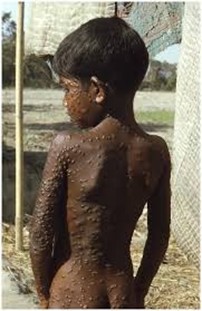

Smallpox was one of the most devastating diseases known to humankind. Caused by the variola virus, it was highly contagious, spreading primarily through close human contact. Its symptoms began with fever, body aches, and mouth ulcers, followed by the appearance of a distinctive rash that developed into fluid-filled pustules. Survivors often bore permanent scars, while many suffered blindness as a complication. The disease was also infamous for its mortality: the more virulent strain, variola major, had a fatality rate of about 30%, while the less severe variola minor was associated with a lower, though still significant, death rate. Globally, smallpox was responsible for an estimated 300 million deaths in the 20th century alone, with about 15 million cases occurring annually up until the late 1960s (WHO, 2024; CDC, 2020; Wikipedia, 2024).

Nigeria, as Africa’s most populous country, was a critical battleground in the fight against smallpox. In West and Central Africa, including Nigeria, the average fatality rate reached 14.5%, with the highest burden borne by infants and the elderly (Fenner et al., 1988; Henderson, 1987; Breman & Arita, 1980). These figures underscored the urgent need for an effective national and regional strategy.

The eradication of smallpox in Nigeria was part of the broader West African Smallpox Eradication and Measles Control Program launched in 1967, supported by the World Health Organization (WHO) and international partners. While initial campaigns relied on mass vaccination, the turning point came with the adoption of ring vaccination—a method in which vaccination was targeted to the immediate contacts of confirmed cases, thereby creating a buffer that prevented the spread of the virus. This strategy, combined with active surveillance and rapid containment, allowed Nigeria to interrupt smallpox transmission by the early 1970s (WHO, 1980; Foege, 1976; Indiana University Libraries, 2020).

Globally, the last natural case of smallpox was recorded in Somalia in 1977, and in 1980, WHO officially declared the disease eradicated. Smallpox thus became the first human disease to be completely eliminated through vaccination—a milestone in global public health history (WHO, 1980).

The eradication of smallpox brought enormous benefits. First, it eliminated a disease that had once been nearly a “death sentence,” thereby saving countless lives. Second, it resulted in significant financial savings. Countries no longer had to budget for routine smallpox vaccination campaigns or quarantine systems, with economic analyses showing that eradication efforts quickly repaid their cost. For instance, it is estimated that the United States recouped its entire investment in the global eradication programme every 26 days after the declaration of eradication (Pan-Nigeria, 2024; Fenner et al., 1988). Third, the global effort strengthened health systems, improving surveillance, outbreak response capacity, and cross-border collaboration.

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of smallpox eradication in Nigeria is its influence on other immunisation activities. The success of smallpox eradication demonstrated that even the most entrenched diseases could be defeated with vaccines, coordination, and persistence. This laid the foundation for the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) launched by WHO in 1974, which aimed to extend the benefits of vaccination to children worldwide. Since its launch, EPI and subsequent immunisation programmes have saved an estimated 154 million lives globally, with measles vaccination alone accounting for nearly 94 million lives saved—many of them children under five (WHO, 2023; Wikipedia, 2024).

In conclusion, Nigeria’s experience in eradicating smallpox remains a beacon of hope and a foundation for immunisation activities. It proved that with strong surveillance, innovative strategies like ring vaccination, and coordinated leadership, even the deadliest diseases could be conquered. Today, as Nigeria battles to eliminate polio, control measles, and introduce new vaccines such as the measles-rubella (MR) vaccine, the smallpox story continues to inspire and guide public health action. The eradication of smallpox was not just the end of one disease; it was the beginning of a global belief in the power of vaccines to transform lives and societies.

References

- Breman, J. G., & Arita, I. (1980). The confirmation and maintenance of smallpox eradication. The New England Journal of Medicine, 303(22), 1263–1273.

- CDC. (2020). The Eradication of Smallpox. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from cdc.gov

- Fenner, F., Henderson, D. A., Arita, I., Jezek, Z., & Ladnyi, I. D. (1988). Smallpox and Its Eradication. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Foege, W. H., Millar, J. D., & Henderson, D. A. (1976). Smallpox eradication in West and Central Africa. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 54(6), 661–673.

- Henderson, D. A. (1987). Principles and lessons from the smallpox eradication programme. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 65(4), 535–546.

- Indiana University Libraries. (2020). Smallpox Vaccine: A Global Public Health Triumph – West Africa. Retrieved from collections.libraries.indiana.edu

- Pan-Nigeria. (2024). Immunization in Nigeria. Pediatric Association of Nigeria. Retrieved from pan-ng.org

- WHO. (1980). The Global Eradication of Smallpox. Final Report of the Global Commission for the Certification of Smallpox Eradication. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- WHO. (2023). Expanded Programme on Immunization: 50 years of saving lives. World Health Organization.

- Wikipedia. (2024). Smallpox; Expanded Programme on Immunization. Retrieved from en.wikipedia.org